She's Beautiful When She's Angry features activists who were at the heart of the early women’s movement. In every city, in every state, thousands of women fought to change the world. Here are some of their stories.

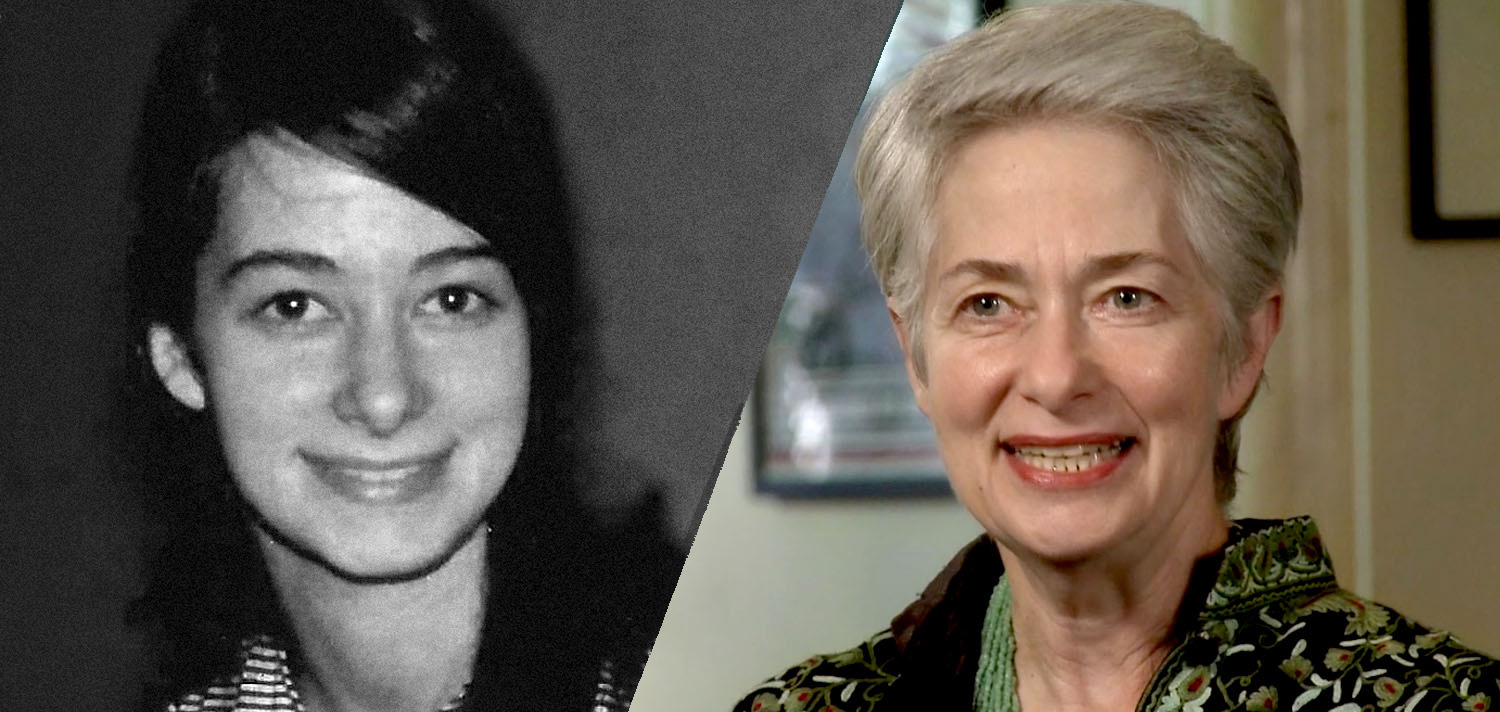

“When we started NOW, we knew the world needed a civil rights organization, some of us called it an NAACP for women, to work for women’s rights. And that’s one reason it exploded so powerfully—because it was long overdue, in some ways it was centuries overdue.” Read Bio

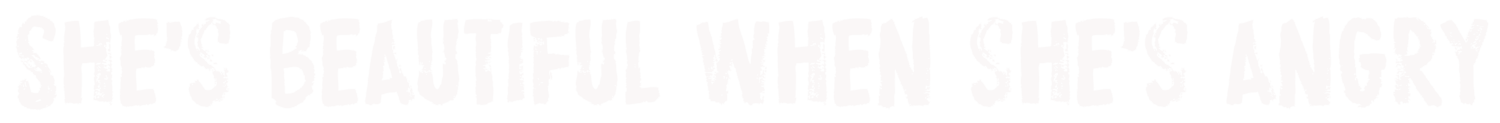

“In the 1960’s we were all subjected to a double message: that first of all sex was okay now, but if we were pregnant it was our problem. Abortion of course was totally illegal and very hard to get. The HORROR—the fear of pregnancy—loomed over anything one did.” Read Bio

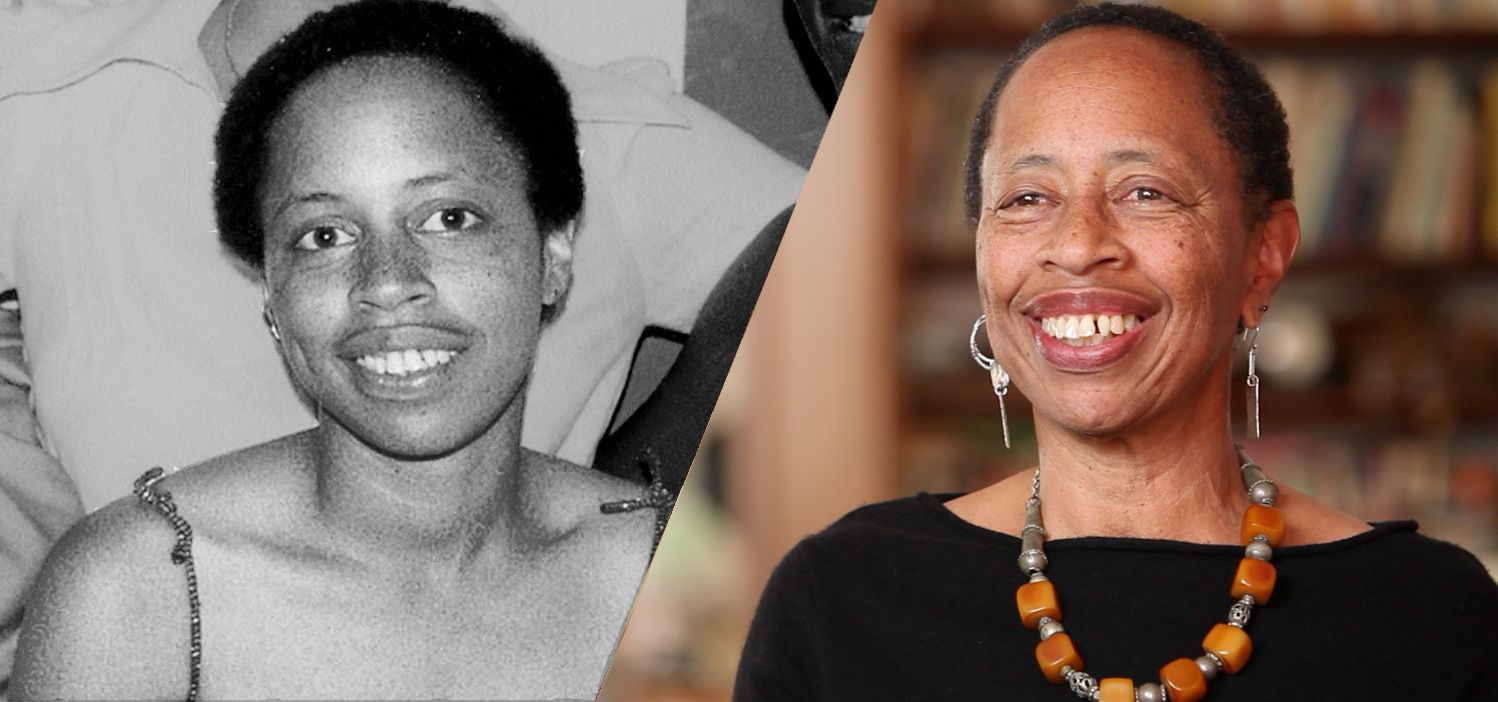

“I was with SCLC—the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—in the South. Many of us who started this new movement had come out of civil rights, and absorbed its ideas, so that it shaped the women’s movement. In some ways, the women’s liberation movement was the bastard child of the civil rights movement.” Read Bio

“The first NOW meeting I went to was in November 1967. We were dying to get things done, I cannot tell you the passion we had. Stop with all this talk, we wanted to do something!” Read Bio

“In Washington we were like, ‘have demonstration will travel.’ We demonstrated in the halls of Congress, we demonstrated outside of Congress. We said, ‘we are not asking men for our rights, we are taking them.’” Read Bio

“I was in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. You’re talking about liberation and freedom half the night on the racial side, and then all of a sudden men are going to turn around and start talking about putting you in your place. So in 1968 we founded the SNCC Black Women’s Liberation Committee to take up some of these issues.” Read Bio

“We were very conscious of race and class, because of Washington being a multi-racial city. Lots of working-class women were there in hospitals and government—just for the taking. We went and talked to them all! And all of these women responded so incredibly! It was like, ‘Yeah! Yeah! Come talk to us!!’ It was a bonanza of organizing.” Read Bio

“A friend mentioned his sister was pregnant, nearly suicidal, and needed an abortion, so I helped find her a doctor. A few weeks later, someone else called…the word had spread. I was living in a dormitory, so I told people to call and ask for Jane. In those days, three people discussing an abortion was a conspiracy to commit a felony murder.” Read Bio

“In JANE, the underground abortion service in Chicago, all of us were always aware that what we were doing was illegal, that we could go to jail. We worked to keep a lot of what we did secret, literally underground. We knew these women are desperate, and they are going to hurt themselves and do awful things if they cannot find people to help them.” Read Bio

“My mother was very proud of having participated in suffrage marches around Chicago, and when I was a little girl she would always take me with her to vote. I decided later on that the two emancipators of women were the vote and birth control, the ability to control your fertility.” Read Bio

“It’s really hard to imagine how shameful sex was. You had to put on a wedding ring and pretend you were married to get birth control. So suddenly being in a room full of women who were eagerly speaking of sex—not for the titillation, but in order to be able to change this double standard—was a very great thrill.” Read Bio

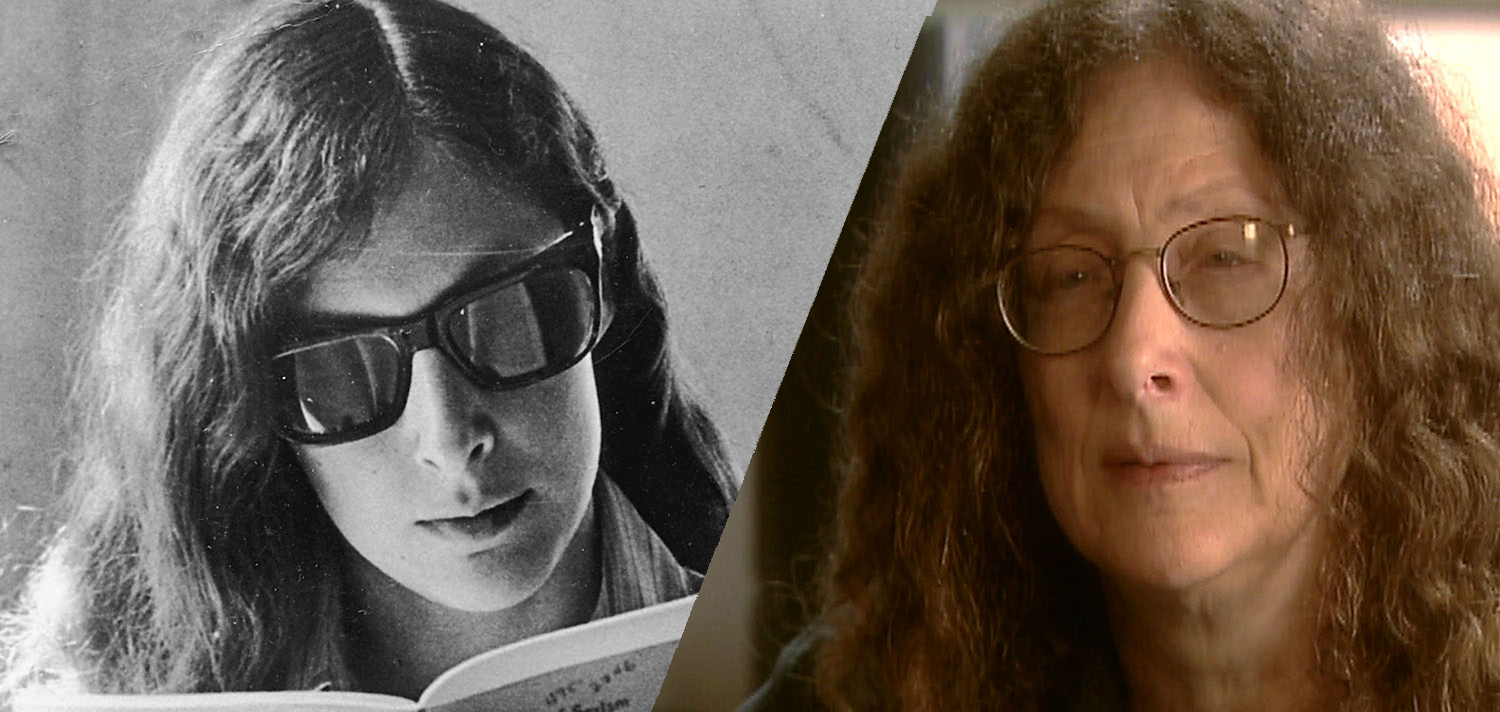

“We began to realize that we knew nothing about ourselves. I was in the history department at Berkeley and I knew zip, nada, zero about women’s history. We realized we didn’t know very much about women as a social group, or women’s literature, or women’s art.” Read Bio

“It was thrilling, absolutely thrilling, and hard. You have to take yourself seriously, and nothing in this culture encourages you to take yourself seriously. In the beginning of the women’s movement, women as well as men told me I was wrong. Over and over again. ‘You are wrong, women are not oppressed.’” Read Bio

“I told no one I went to college with that I was a lesbian, I never told anyone. I think that was what the 60’s were like for many of us—we grew up in silence and isolation, and that’s why consciousness-raising in Redstockings was so appealing, because so much of our lives we could not speak of.” Read Bio

Our Bodies, Ourselves Collective

“We came together with a passion for a project. We would do a course on women and their bodies, and if women were excited about the material, they would take it into their communities, their neighborhoods and just pass on the information.”—Miriam Hawley. Read Bio

Our Bodies, Ourselves Collective

“People who had post partum depressions worked on the post partum chapter. People who had abortions worked on the abortion chapter. We always said the personal is political, the political is personal and there it was.”—Vilunya Diskin. Read Bio

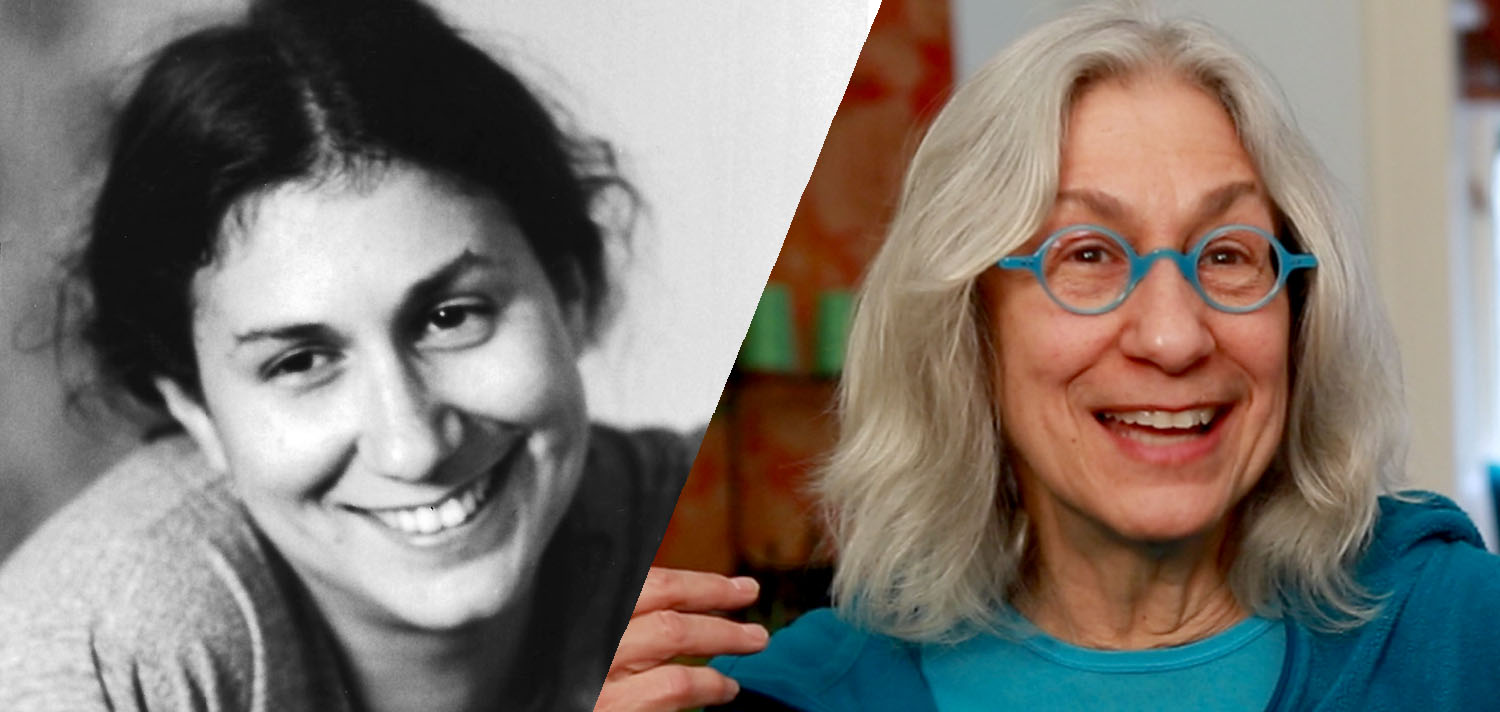

“At the Miss America protest, people outside had all kind of signs. I liked mine best, ‘Can makeup cover the wounds of our oppression?’ But the best part came when they were about to crown Miss America. Women who’d snuck up into the balcony unfurled this huge banner that said Women’s Liberation, and it was a beautiful moment.” Read Bio

“Everybody was eager then to talk about women’s liberation. And all these writings, they were very precious to us, like 'Notes from the First Year,' and the 'Second Year,' because they were the vanguard. We were changing the relationship between male and female. Nothing is more basic than that.” Read Bio

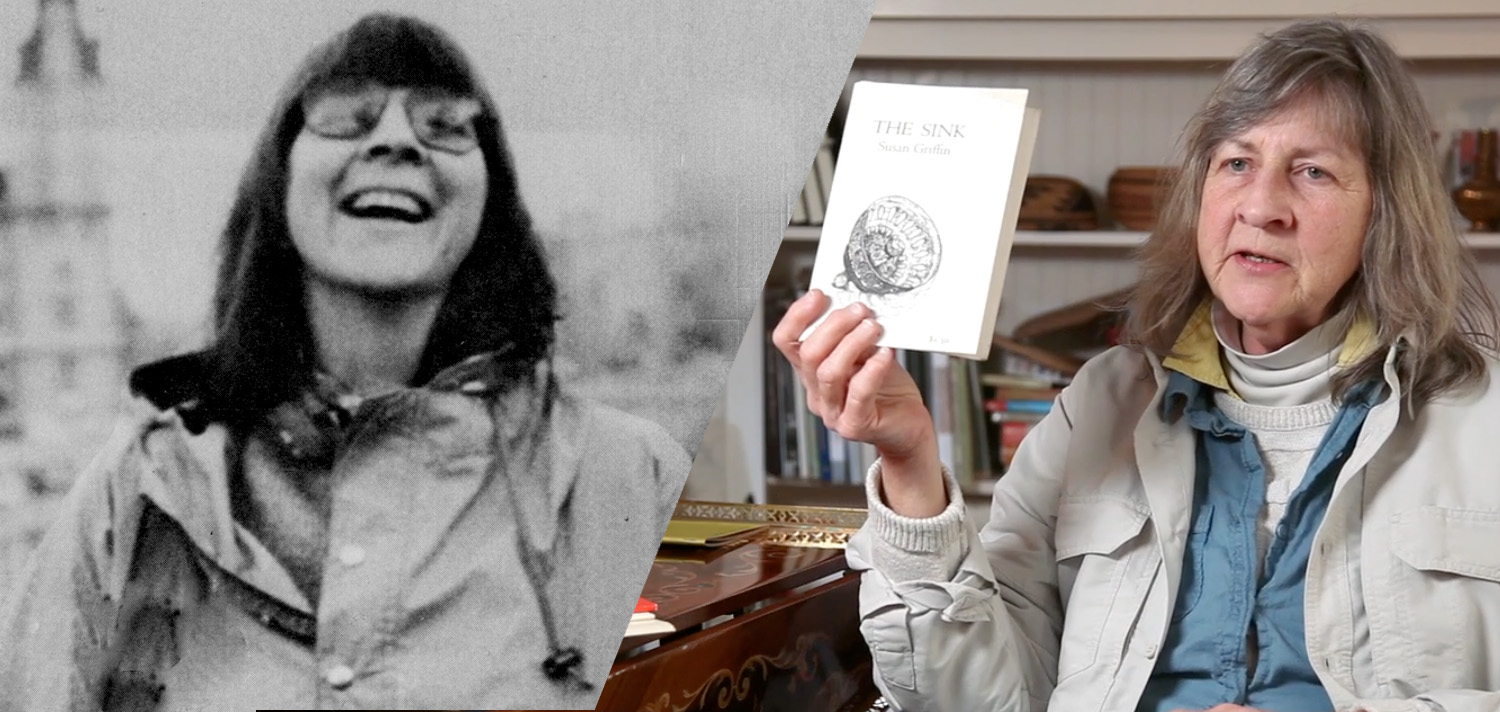

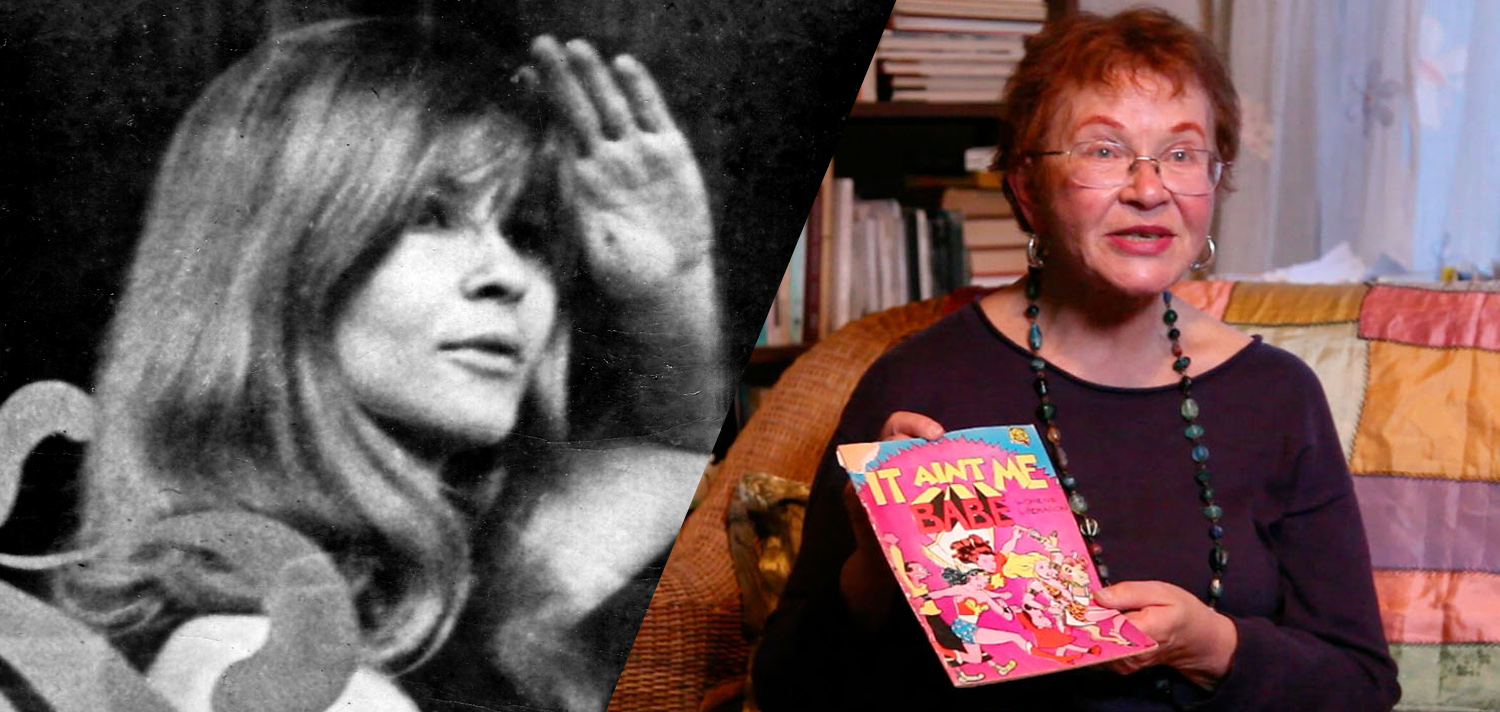

“I saw the first issue of It Ain’t Me Babe, and I immediately phoned them up and said, ‘Hi, I’m an artist and I want to work with you.’ It was so exciting that there was actually a women’s liberation newspaper! Because I had these women standing beside me for moral support, I was able to do the It Aint Me Babe comic—the very first all-women comic book in the world!” Read Bio

“I was in the Young Lords, and one of the points in the original program was ‘Revolutionary Machismo’. Machismo is reactionary, so you can’t have revolutionary machismo. We women weren’t having it. So we made a very different kind of statement. ‘We want equality for women. Down with machismo and male chauvinism.’” Read Bio

“I joined NOW, and I was the youngest person there and I think I was the only southerner. I called them on the carpet about class, and I called them on the carpet about race, and then I called them on the carpet about lesbianism, I said, ‘You are treating women the way men treat you. And those women are lesbians.’” Read Bio

“We took seats all around the conference, and when the lights went back on—like Superman, we removed our blouses and stood up wearing our Lavender Menace t-shirts. We started saying that we were taking over the meeting and the women’s movement had to address the issue of lesbianism.” Read Bio

“We started Black Sisters United, and it was basically a consciousness-raising group. We were struggling to understand what was different about our perspective on women’s place in the world from what we were hearing from the mainstream women’s movement. And we couldn’t have that conversation in spaces that were majority white women.” Read Bio

“Those of us who planned the Ladies’ Home Journal sit-in understood that there was something essentially hilarious about 200 women sitting in at a women’s magazine and claiming it didn’t reflect the interests of women.” Read Bio

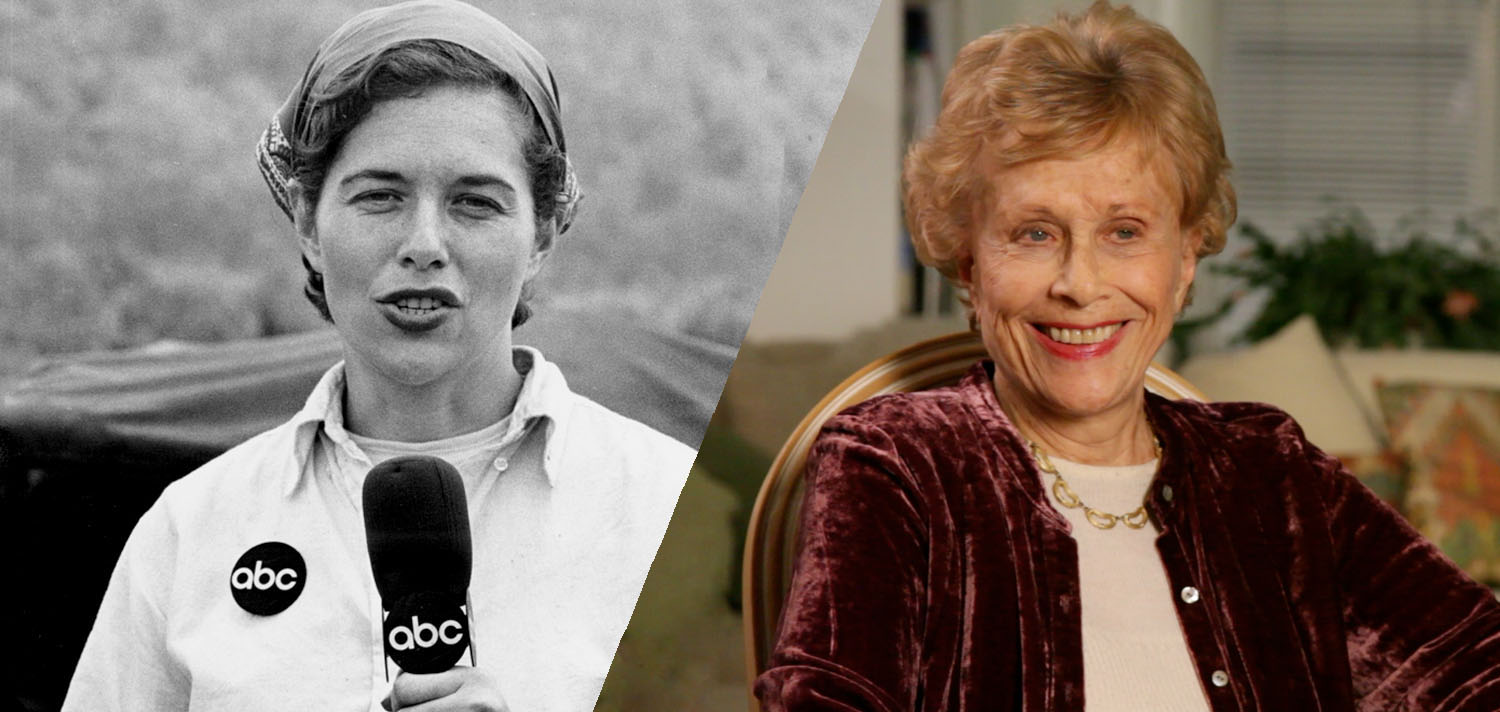

“I may have looked very proper and buttoned up as a reporter, but I was very sympathetic to what was going on. Now it isn’t my taste to do some of the demonstrations and things some of them did. But I was always sort of gleeful about it underneath and I thought, you know, ‘Go for it!’” Read Bio

Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton

“In the early 70’s, after a great deal of effort by feminists, we got close to having a real childcare system. When Richard Nixon vetoed the childcare bill, that was a tragic moment in history. And we’ve been paying for it ever since. I can’t think of a more important issue that early feminists raised than childcare.” Read Bio

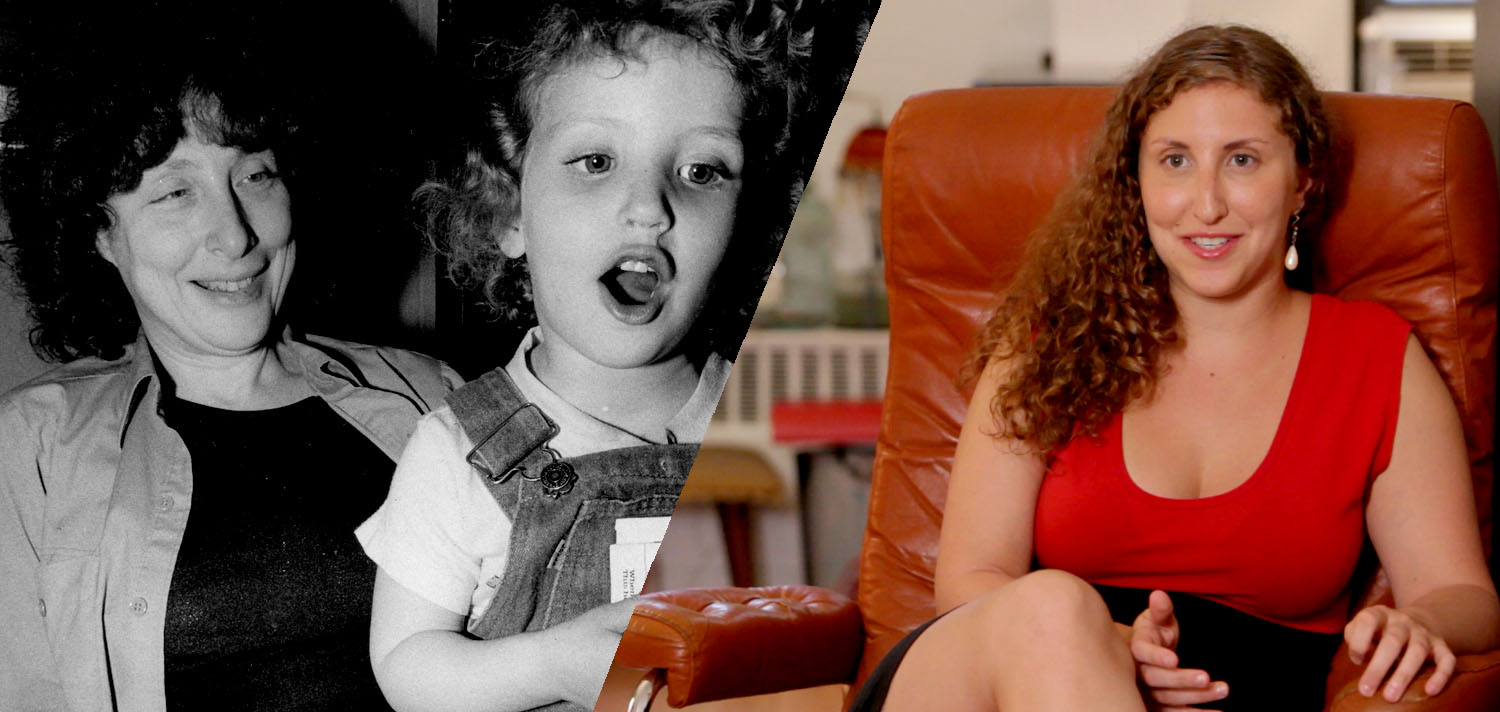

“Though my mother was an early pro-sex feminist, I didn’t really know what feminism meant to me, to our generation. When I wrote Girldrive with my friend Emma Bee Bernstein, we definitely found a lot of young kick-ass feminists out there. They’re blogging. They’re out in the streets. They’re organizing.” Read Bio

“Chicago was a hotbed of feminist organizing. The women power that went into this was amazing, it’s what can be done if people put their energy into something. You can’t convince me you can’t change the world, because I saw it happen.” Read Bio

“Before the women’s movement, you would probably have to tell a lie every five minutes. ‘Oh I’m so happy that I’m just serving you.‘ Constantly telling lies in one way or another, it undermines a life and a soul. Was the civil rights movement worth it? Is liberation valuable? Yes, it’s worth everything you have to pay.” Read bio

"The women’s movement was a revolt that was starting from the bottom, from the grass roots -- nobody controlled it. There are probably tens of thousands of women all over the country right now who were leaders in the women’s liberation movement and we’ll never know their names because they were organizing and agitating in their church, or in their school, or in their neighborhood, or just in their marriage." Read bio

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

“In Cell 16 we decided to make self-defense a priority for organizing, because it seemed really important in Boston. In the summer of 1968 there were mass murders of women, and they were never identified. And the headlines were “More Slain Girls” in the newspapers, on all the newsstands. So we started street patrols for the factories down by the river, where women were constantly being mugged, assaulted and raped. We formed a whole project around rape.” Read Bio